What Got Left Behind

May 31, 2015

And in the beginning, there were no roads. That’s why he was in a boat when he saw the horses walking on water. Beaver Lake in the Kawartha Highlands flows, then dribbles, into Lake Catchacoma. In 1954, Pearson’s Landing was on the west shore of Catchacoma and that’s where we left our car. To get to our cottage at the eastern end of Beaver Lake, you had use a boat – in our case a tiny white wooden dory with a three-and-a-half horsepower motor. Going full blast it took us at least three quarters of an hour to get there.

On the day in question, my father, Eric, had picked up supplies at Pearson’s and was reading a fairly recent newspaper when he looked up and saw draft horses standing on the water in the middle of the lake. Sunstroke? Dirty glasses? No, the horses were standing on a flat barge and were being moved from the logging camp at the end of our lake.

Beaver Lake was tiny until the government (probably in the form of the Department of Lands and Forests), put in a dam on Bottle Creek just north of us, and dynamited a narrow passage between Beaver and Catchacoma. The passage is known as The Cut.

With some tricky dam fiddling, our lakes are used as reservoirs for the Trent/Severn Canal system. Lots of boats use the Trent/Severn locks in the summer and by autumn almost no water trickles through The Cut and Beaver Lake is down so much, we can see what what’s under large beaches.

It could be a Rural Myth, but the dam and the Cut originally caused a lot of water to build up in Beaver Lake and drown ten to twenty feet of the forest surrounding the lake. So when the first potential cottagers arrived, by boat, they had to make it through a tangle of stumps, fallen trees, brush, guck on the bottom and the biggest goddamn hairy black spiders the size of a gorilla’s hand you’ve ever seen. These creatures are now smaller and you know them as dock spiders. Most of the women folk wondered what the hell their husbands had bought. Remember, this was the early 1950s.

You had a short time to clear a channel — to get to the land — that you had to clear — to build a tiny cottage – using only hand tools. Because, along with no roads, there was no electricity.

From left to right: Sister Debby waits for Eric to load lumber at Pearson’s Landing. Eric builds with no electricity.

In spite of the lack of things, there was camaraderie and a community. A path was worn from cottage to cottage. At night, my mother used to narrow her eyes to follow a flashlight beam along the path on the opposite shore. She figured out who was tiptoeing through the bush for an illicit hanky-panky meeting. It was that kind of community. Snoopy.

None of us owned the lumbering rights but the logging company was no longer allowed to cut trees on our land. After all, we’d bought it. Eric had to borrow the money to pay $51.60 for .93 of an acre with three hundred feet of shoreline determined by the spring high water mark. As the summer went on and the lake went down, Eric owned more and more shore – until next spring.

The lumber company had left behind huge stumps — probably first growth trees cut just before the cottagers bought their pieces of virgin forest. Ha. For many springs, we’d arrive to have a log boom holding the past winters’ harvest. At least a third of the lake’s surface was floating logs. They’d been cut from the forest behind the cottagers’ land. We never did see the logs going to the mill at the end of Mississauga, another lake on the chain. But we did see escaped floaters.

The cottage men scrambled to drag the floaters to their pieces of shoreline. Earlier, they’d pulled out the stumps of the original drowned tree to make openings for their boats to reach their land. And as soon as those stumps with their roots were gone, the lake started eating away at the land.

Those half-sunken salvaged logs were shoved into the crumbling shore. Every winter, the ice would grab a log or two and truly sink them. They melded with the hidden underwater stumps … and the water continued to go down every summer.

No boats skimmed the water here. It was caution with a lookout or you’d shear a pin. Not a PIN. In those days, a pin was a small piece of brass that kept the prop on. Propeller to you urban types– the spinning thing that moves the boat.

The men folk got together and put out markers. Then they had a beer. Then they blasted The Cut a bit more. Then they had a beer. They formed a cottagers association, held an annual regatta and obviously liked each other.

I was nine and my sister was three. We took the path to the end of Beaver Lake where the lumber camp was. It had kittens. And horses in a barn. And even in the summer there was a cook. He gave us pieces of fresh pie and my sister would try and catch a bird by putting salt on its tail. Real sense of humour that cook had.

If the boats were home made and lumpen, the first cottages were squat, often built from the local mill’s lumber. Ahh the cycle of nature demonstrated by our great Canadian renewable resource, the forest. Lucky for us, aluminium storm windows had just been invented so our city neighbours’ old wooden storms were collected and slotted into our eight-foot walls (the length of a two-by-four).

Beaver Lake evolved. The beavers moved out of their lodge but left their name behind. Keith, next door, bought a gas-powered cement mixer and where everything was wood, Keith poured the ugliest concrete fireplace now known as The Mass. After the apocalypse, that fireplace will soar above the ashes like the monolith in the movie “2001”.

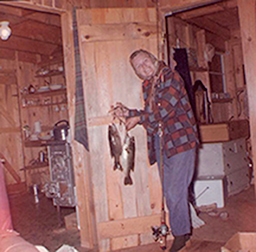

My mother bought a tiny oven to sit on top of her coal oil stove and made cookies. A saint. My mother also caught a lot of fish and cooked them. It was the main protein in our diet of canned staples. I’ll never forget the sight of a can with its lid off and a whole cooked chicken inside. The skin was gross. Betty’s Catch of the Day was better. No contest.

Eventually the lumber camp was abandoned. The windows were all smashed in and a lake bad-boy blamed me. But the adults knew I hadn’t been around that weekend and no one ever trusted him again.

Then along came electricity. And a fridge. No more sour milk sitting on melting lake ice from Pearson’s in our wooden icebox. An electric pump brought water from the lake to the cottage instead of me running back and forth with a bucket. Cottages got bigger with power tools. CB radios came in and my mother followed the neighbours comings and goings by not announcing herself. Come in Road Runner. No answer from Road Runner. Just a little snicker to herself.

There was time to sit back and enjoy a drink. Or two. The dads had mostly finished building and they didn’t know what to do with their time. Eventually, Alcoholics Anonymous became big in many lives and card games became alcohol free.

The electricity made the biggest change, not the roads. When the roads came in – based on the old logging road behind us – everyone just hauled in more junk, along with large boats on trailers, and those small-but-loud four-wheel vehicles. The roads did shut down most of the landings. Landings? What’s a landing? Now we have a couple of marinas. Pearson’s is no more. Nor is the sense of a brand new community, not to mention the variety in the gossip.

As I sit here on this long weekend, thin silvery boats fly down our lake. Beaver Lake at this end doesn’t go anywhere – just the meadow where the lumber camp used to be. So the boats turn and speed back – creating even more wakes to undercut the shoreline and leave the water murky. The silly personal watercrafts weave back and forth, and the guy trying to sail is terrified by it all — judging from the number of times he just lets go of the sail.

The Harris government turned the swampy forest around us into Kawartha Highlands Signature Site, a sprawling Ontario Provincial Park. Hunting and commercial trapping are still allowed. Vehicles pour down the Beaver Lake Road to one of the large parking lots, across from the old lumber camp entrance.

That tell-tale flashlight weaving along the path through the bush after midnight is no more. The new cottagers don’t like anyone walking across their property. No one needs to borrow a handsaw. Next week is the annual Beaver Lake Cottagers Association meeting. Closing the Association for lack of interest is on the agenda.

Only the rusting oil tank remains in the lumber camp. My parents left their old white dory rotting on the shore. We can’t bear to throw it away or burn it and besides, it irks the tidy neighbours who have lawns to mow. No one eats the fish — if they even catch any. And if they do, they kiss the poor fish and throw it back into the lake to be tortured again, by someone else.

This weekend, new people asked a long-time resident not to fish opposite their dock. They’re trying to teach their little girl not to do that sort of thing. I hope they remember this when she’s unable to sit, still and quietly, on a calm lake, and listen to the loons. That’ll be about the time she’s old enough for drugs, booze, all night parties and fast boats. Young people have died on these lakes.

The hydro often goes out during storms and you hear the generators kick in around the lake. Sitting on our dock is like being in a busy laundromat. Cottagers tell me the generators keep their food from going off. Shades of our old icebox.

I try to sympathise. But — how much does a generator, and its installation cost compared to the food that can’t be eaten. And how much fuel burning into the atmosphere does it take to equal a fridge with sour milk, defrosted steak and slimy tofu? The generators also power the flat screens that light up the night with that outer space blue glow. I sit beside five candles and read. It’s still pretty gosh-darn idyllic. Definitely $51.60 well spent.

My mother, Betty, took this first landing photo. That’s me, with my father Eric holding my sister Debby.

Eric, white dory & Vauxhall

Wow. This was just like sitting with you at the table in the twilight, sipping the last of the wine, just in time for Tales of the Lake. Your published version is like a best-of-the-best version, minus the buzz of the bugs, and the occasional firework from the other side of the lake. Thanks for writing it down.

p.s. the photos are fabulous, especially that one of you, your dad, and sister by the stump.

h

thank you for reading it and leaving the lovely comment b

I just finished reading your article about the lake. I enjoyed it a lot, you are such a good storyteller. I could see it all, the landscape, the people. I love the first picture of the lake. It is so beautiful, so dreamlike.

J.

After all these years and small stories, a little history, sides, comments… I have a real mental image of the lake. I think I need to visit to have the image of the cottage today. And you in it.

I like your blog, Barbara. It makes me feel as if we’ve had a visit. It doesn’t replace an actual visit.

Nice story. Thanks for sharing your history. You mention the lumber camp on Beaver Lake. Do you recall where the actual mill was? I read that Peterborough Lumber built a huge mill on Catchacoma Lake in 1943 and closed in 1966. Any idea exactly where that mill was? I guess during those years they cut every tree around for miles, so everything we see is second (or third?) growth from then.

Thanks

Rob

What wonderful memories of a time gone by. When neighbour’s you hardly new dropped by to give a helping hand to whatever project was under way. A time when there was a passion associated with where you where. Board games, card games and friendships that developed and lasted a life time. My recollections don’t go back quite that far but after some fifty years and many living on the system-fond memories rekindled.

Thanks